“Champions don’t do extraordinary things. They do ordinary things, but they do them without thinking, too fast for the other team to react. They follow the habits they’ve learned.” –Tony Dungy

The quote above comes from The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business by Charles Duhigg. This book is a fascinating look at habits—what they are, how they form, how they affect us, and how can we choose our habits.

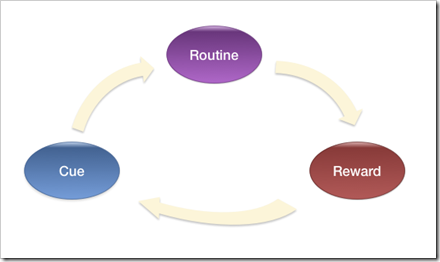

The Habit Loop

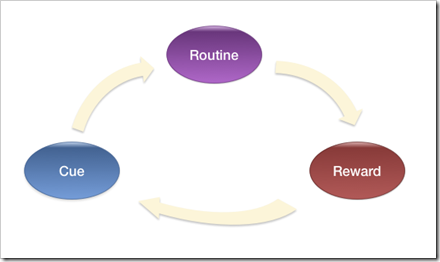

Most of us are barely aware of the habits that make up so much of what we do, but psychology and neuroscience researchers have made great progress in understanding how habits form.

At the core of this research is what Duhigg calls the habit loop. We usually have no trouble identifying the routine, which is what we think of as the habit itself. The value comes from identification of the two other elements of the habit loop.

The first insight comes in realizing that habits are driven by some kind of reward. The reward could be virtually anything–relief from boredom, sense of completion, etc. As our behaviors result in the reward we seek repeatedly, our brains literally restructure themselves. Our brains move the instructions for performing the actions needed to invoke the reward to areas that can operate without our conscience thought. Our habits become become so deeply encoded that they become almost impossible to separate from who we are.

As our behaviors result in the reward we seek repeatedly, our brains literally restructure themselves. Our brains move the instructions for performing the actions needed to invoke the reward to areas that can operate without our conscience thought. Our habits become become so deeply encoded that they become almost impossible to separate from who we are.

The second insight comes in recognizing that there are particular cues that trigger the routine in pursuit of the reward. Cues could be just about anything as well–a feeling of boredom, the sight of a particular object, the presence of a particular person, etc. Identifying these cues are key to understanding and changing our habits, but you’ll have to read the book for that.

Keystone Habits

Studies have documented that families who habitually eat dinner together seem to raise children with better homework skills, higher grades, greater emotional control, and more confidence. Making your bed every morning is correlated with better productivity, a greater sense of well-being, and stronger skills at sticking with a budget. It’s not that a family meal or a tidy bed causes better grades or less frivolous spending. But somehow those initial shifts start chain reactions that help other good habits take hold. If you focus on changing or cultivating keystone habits, you can cause widespread shifts. However, identifying keystone habits is tricky. To find them, you have to know where to look. Detecting keystone habits means searching out certain characteristics. Keystone habits offer what is known within academic literature as “small wins.” They help other habits to flourish by creating new structures, and they establish cultures where change becomes contagious.

Keystone habits are the drivers that lead to other habits. For example, studies have shown that people who adopt the habit of regular exercise find that seemingly unrelated areas of their lives change for the better (being more productive at work, smoking less, being more patient with their kids, etc.).

Small Wins

Small wins are exactly what they sound like, and are part of how keystone habits create widespread changes. A huge body of research has shown that small wins have enormous power, an influence disproportionate to the accomplishments of the victories themselves. “Small wins are a steady application of a small advantage,” one Cornell professor wrote in 1984. “Once a small win has been accomplished, forces are set in motion that favor another small win.” Small wins fuel transformative changes by leveraging tiny advantages into patterns that convince people that bigger achievements are within reach.

Small wins are those sure steps in the right direction that separate high performers from everyone else.

TDD: Keystone Habit of Great Developers

The agile software movement centers around incremental and iterative steps with feedback mechanisms that allow for lots of small adjustments to bring the project to success. So, when I hear Duhigg talk about small wins, it resonates with what we’ve found in building software.

Test-Driven Development (TDD) is the most central of agile practices. It fits Duhigg’s definition of a keystone habit.

TDD and Small Wins

The demands on software developers get bigger and more more ambitious all the time. We presented with complex problems that we generally don’t know how to solve. It is easy to become overwhelmed by the magnitude and get bogged down trying to boil the ocean with code.

The discipline of TDD forces us to methodically break problems down into small chunks. Each passing test is a win and one small step closer to the system the customer needs.

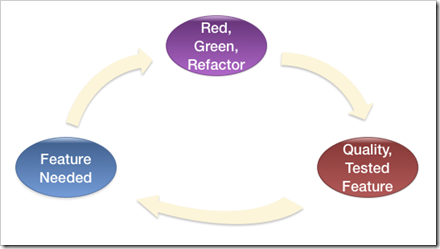

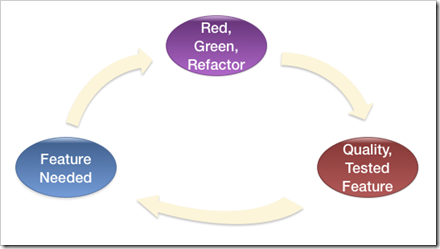

The Cue is obvious: a customer needs a new feature.

The Routine is the well documented (but seldom practiced) red-green-refactor loop.

The Reward is the passing test and a thoroughly executed unit of responsibility completed.

The cycle continues, with small wins coming one after another until the feature is complete.

TDD as Keystone Habit

The TDD habit has many follow-on benefits beyond completed, tested software. Every time we write a test before we write the code, we remind ourselves of several truths:

- If the software is worth creating, it is worth ensuring that it works.

- Each unit of functionality must have a single responsibility and its dependencies must be loosely coupled.

- Keeping the code clean is vital. Keeping it clean is made possible by the protection provided by a comprehensive suite of tests.

- Writing only enough to make the test pass keeps our focus on the customer’s requirement and not a speculative future feature.

I’ve found a common idea emerging among the colleagues that I respect most: we would rather hire a developer that practices TDD and does not have experience in the primary programming language our shop uses than hire a developer with that programming language experience that does not practice TDD.

Language syntax and style is relatively easy to learn. TDD is a keystone habit of great software developers.