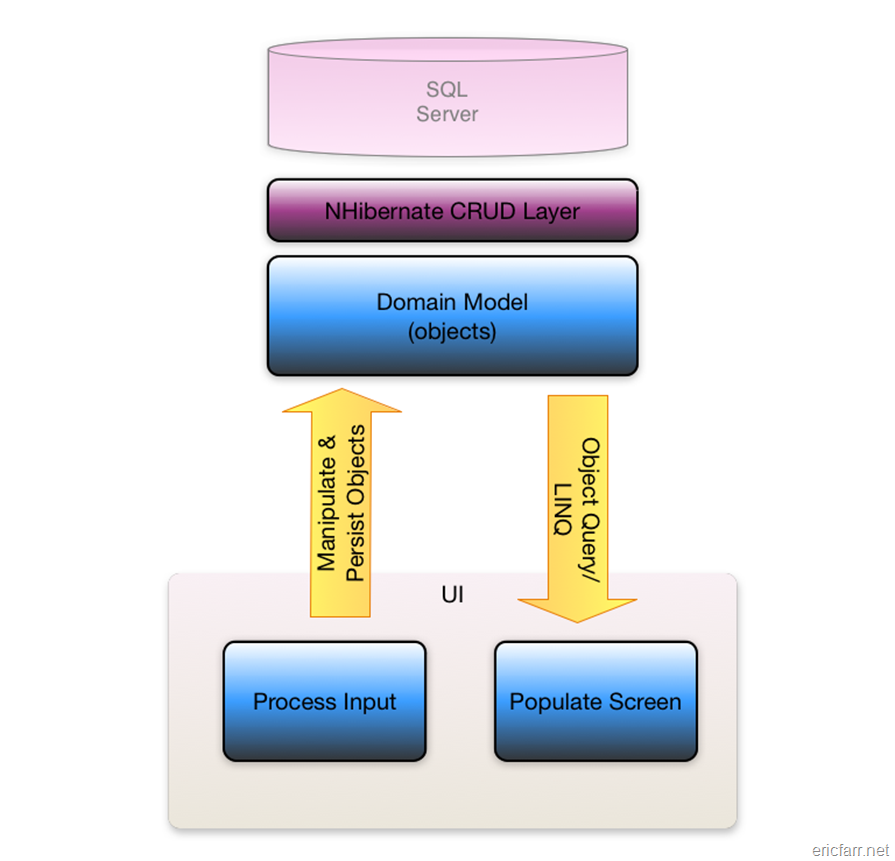

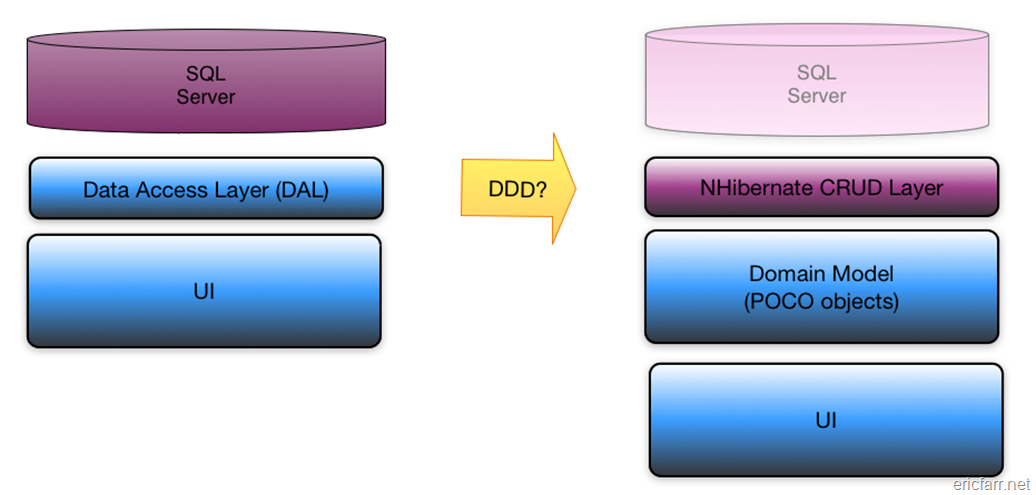

As a long time object-oriented programmer, I was immediately drawn to the DDD concept of Persistence Ignorance. My initial idea of DDD was to simply express the domain concepts in a C# object model, then one one side, map those objects to a persistent store with a technology like NHibernate and on the other side, build a UI without any business logic in it.

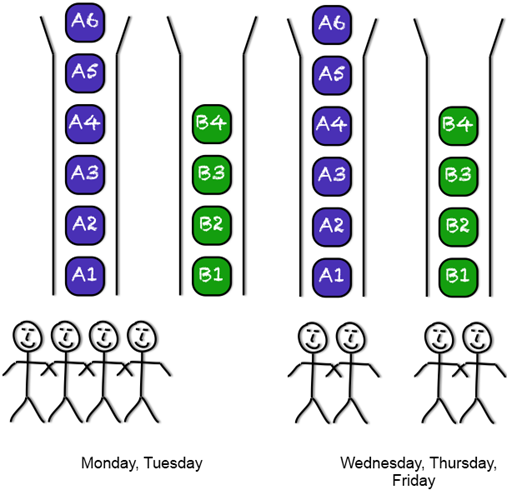

Figure 1: The Naïve Transition to DDD

This was a big improvement over the traditional techniques on the Microsoft stack. Databases are inadequate for expressing domain models and business logic in UIs or databases makes unit testing nearly impossible.

How the Naïve DDD Approach Fails

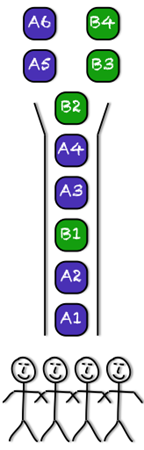

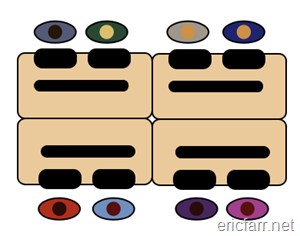

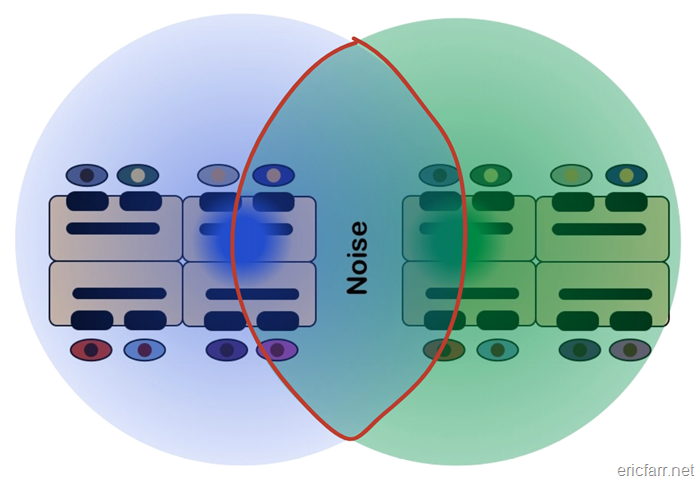

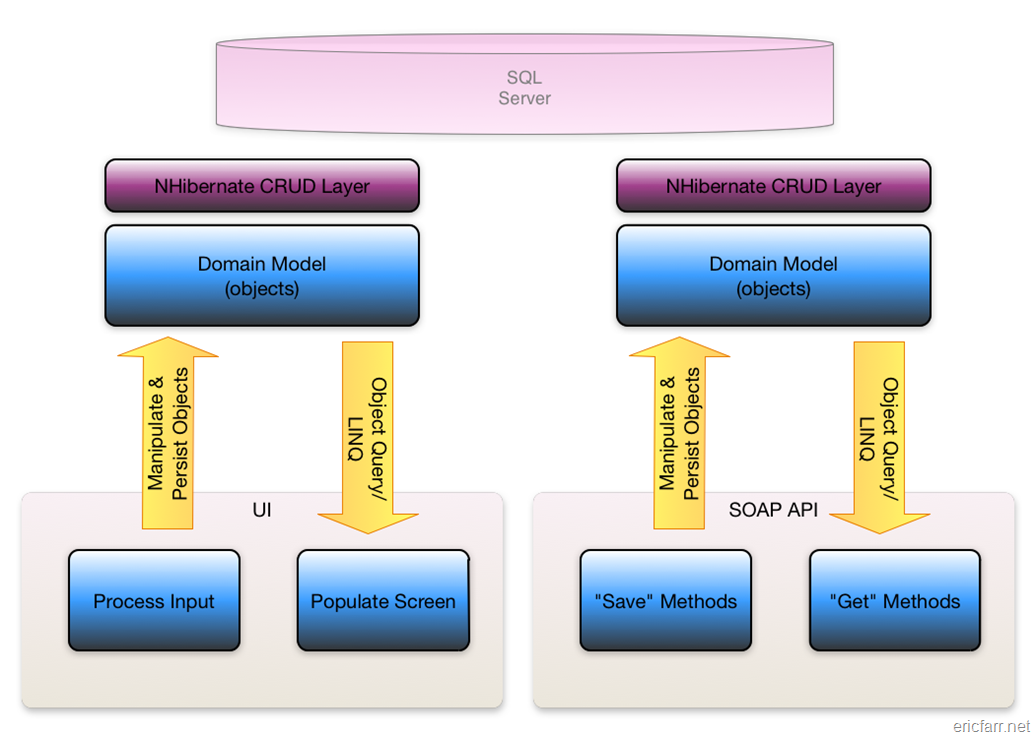

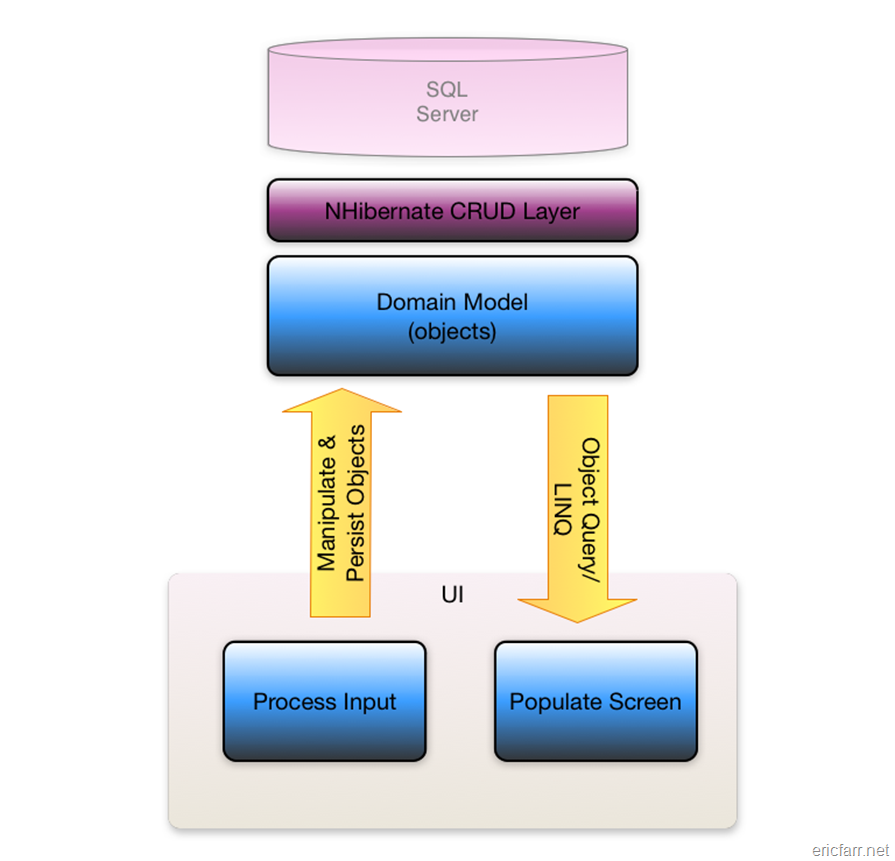

What I didn’t see was that this naïve solution traded one set of problems for another. The new solution looks like Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: The Naïve DDD Approach

This looks OK until you try to build anything remotely complex with this model. The first bit of friction we ran into involved populating some of the screens on the UI. Many screens don’t map smoothly to our rich object model. We get by with technologies like LINQ and lazy loading, but it still feels awkward to spin up a rich object model to simply copy properties to a view.

Things really turn south when we start to have multiple interfaces to the application. Imagine we have our UI and add a SOAP-based API to allow other programs to drive the application.

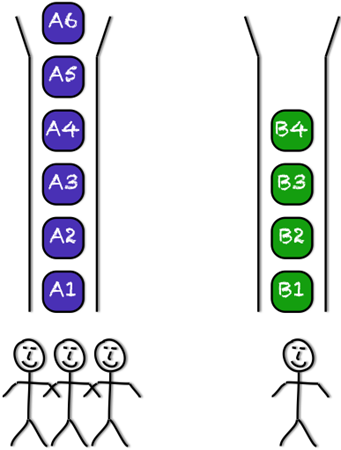

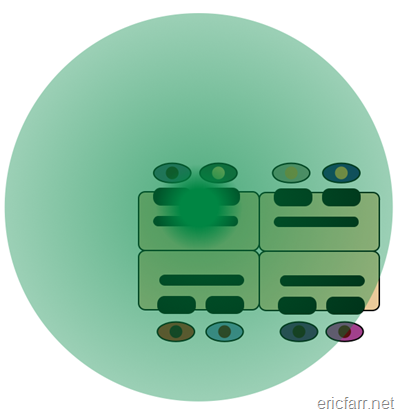

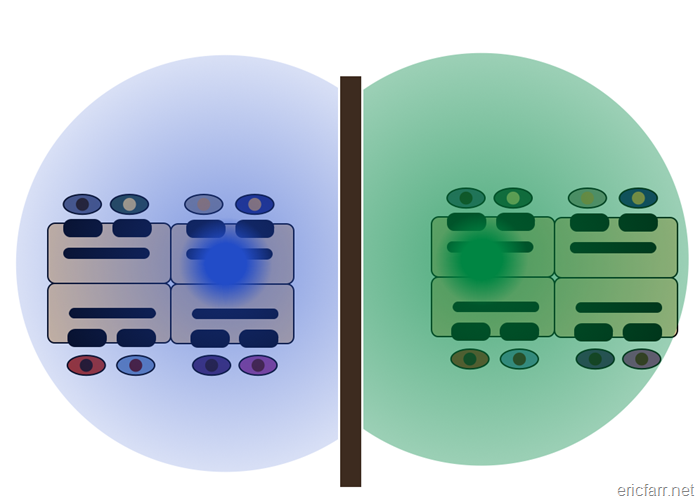

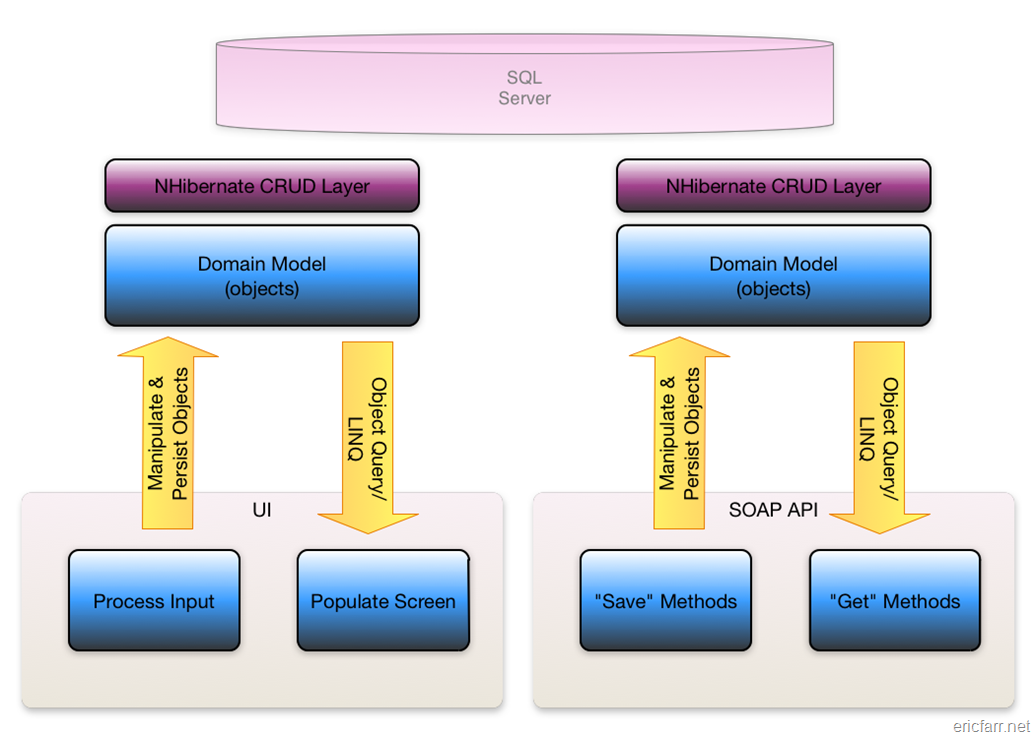

Figure 3: The Naïve DDD Approach with Multiple Applications

Now the CRUD layer really starts causing trouble. First, notice that because our domain model is defined in an assembly (or package or library), it gets deployed to each separate application that needs it. We have a layered architecture, however, all but the database layer get replicated to multiple applications.

CRUD-Based Models and Meaning

Imagine that a user makes a update to the comments on order 0123 through the UI at the same time that an external program calls GetWorkOrder(“0123”), updates the order description, then passes the updated order into SaveWorkOrder. Now both components are instantiating order 0123, copying the updated property values and saving it back to the database.

We lose the intent of each of those two actors. We are left to sort out any conflicts on simply timing and the intelligence of our ORM tool.

You could avoid the replication in Figure 3 by creating a application server, but you would still have the loss of semantically meaningful information that comes with a CRUD-based object model.

Request/Response: Good for Some Things Not for Others

Our Figure 3 architecture is inherently synchronous request/response. Consider the GetWorkOrder Web service method. Our external system calls that method and gets back the specified work order. This is what we want. The calling code cannot continue until the request comes back.

On the other hand, imagine any method that makes any kind of change to the system (like SaveWorkOrder). We would like to be able to queue these changes and allow the system to process them as compute capacity is available. We also don’t want to have to write code to handle the case where the Web service is temporarily not available.

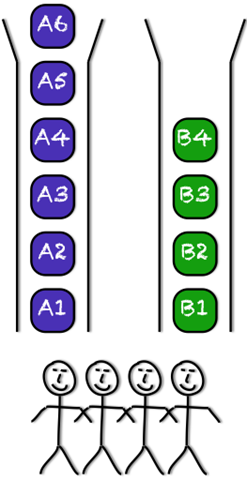

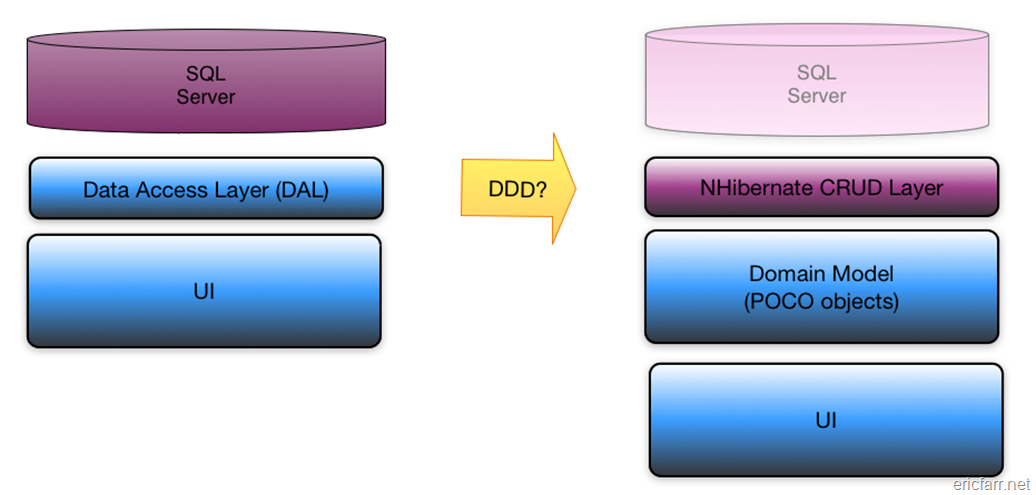

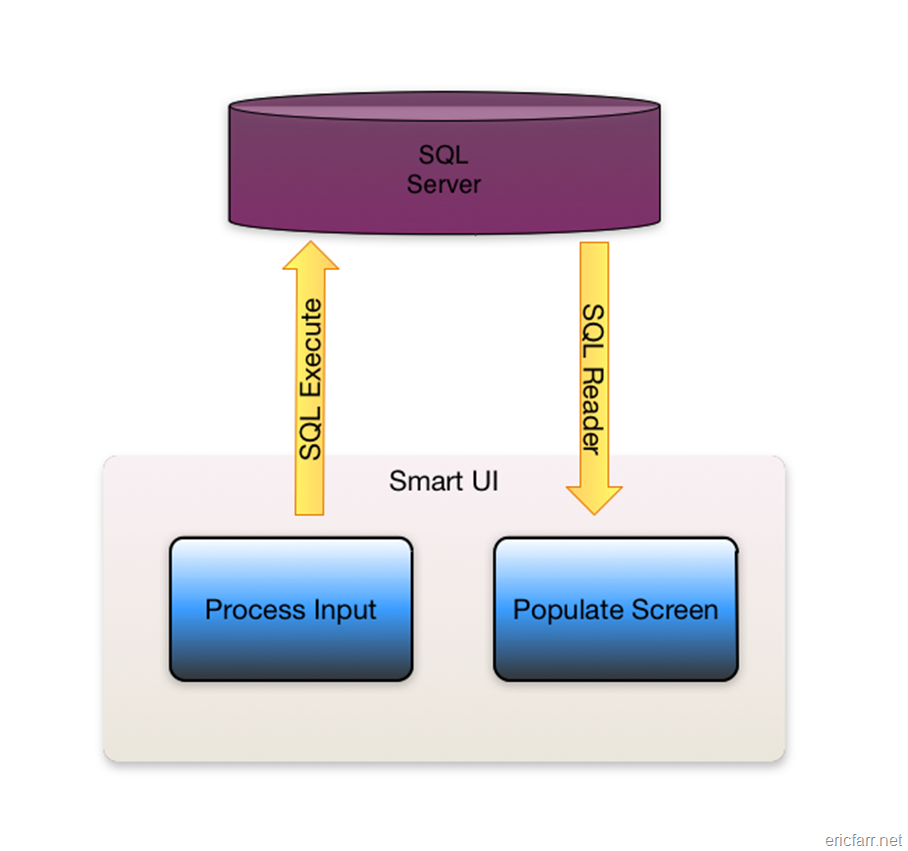

The Old Way Had Some Things Right

Notice that the bad old traditional system does not exhibit some of these problems:

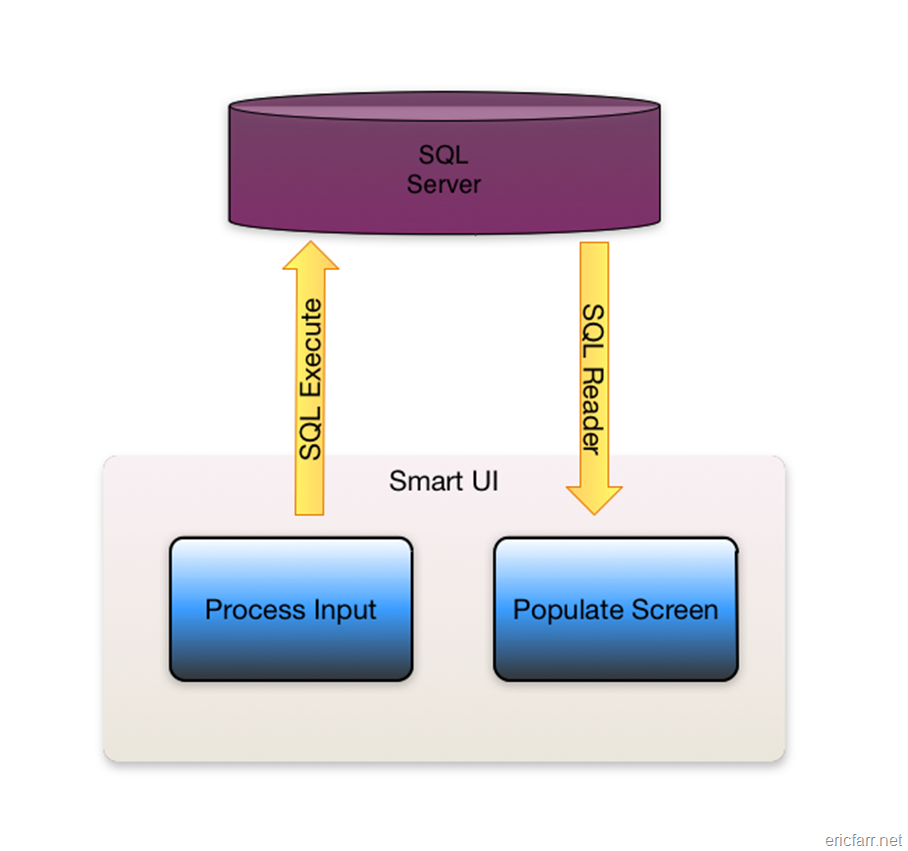

Figure 4: The Old Smart UI Approach

What the traditional system did right was account for updates being different from queries. Reads used SQL queries or stored procedures and views to get exactly what the screen needs—no more, no less. The write side used SQL inserts and updates to make just the changes necessary to accommodate the user’s actions in the UI. You couldn’t test it and you wouldn’t want to be the one to have to maintain it or enhance it, but it performed well and got the job done.

It did, however, have all the same request/response limitations.

Getting it Right with DDD

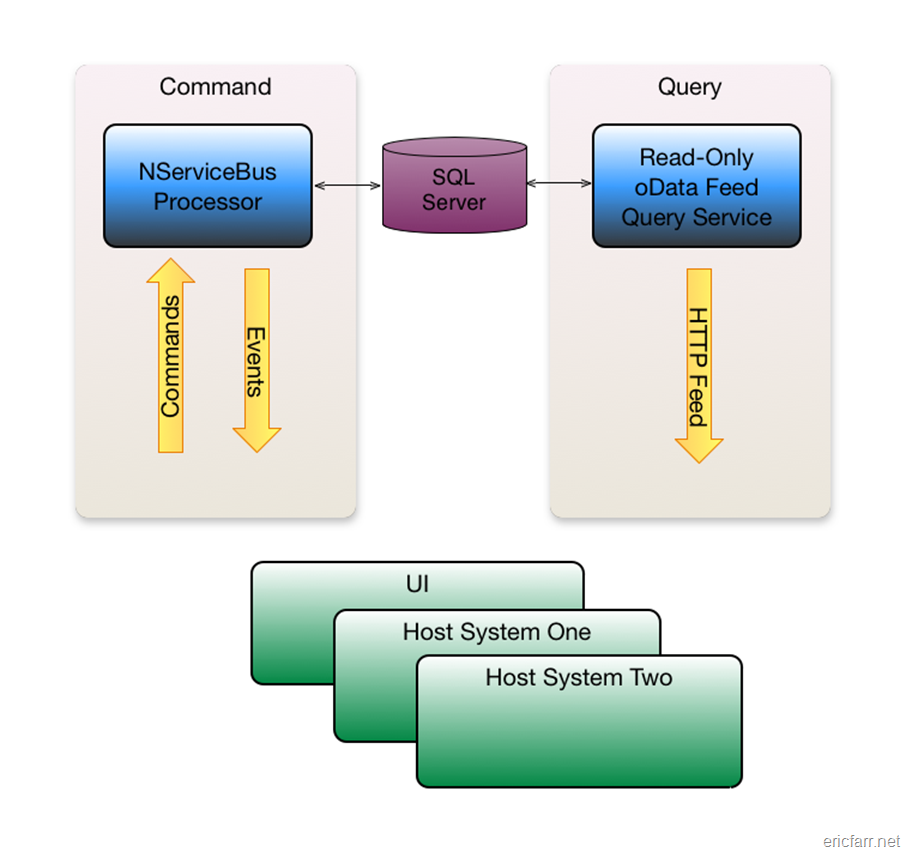

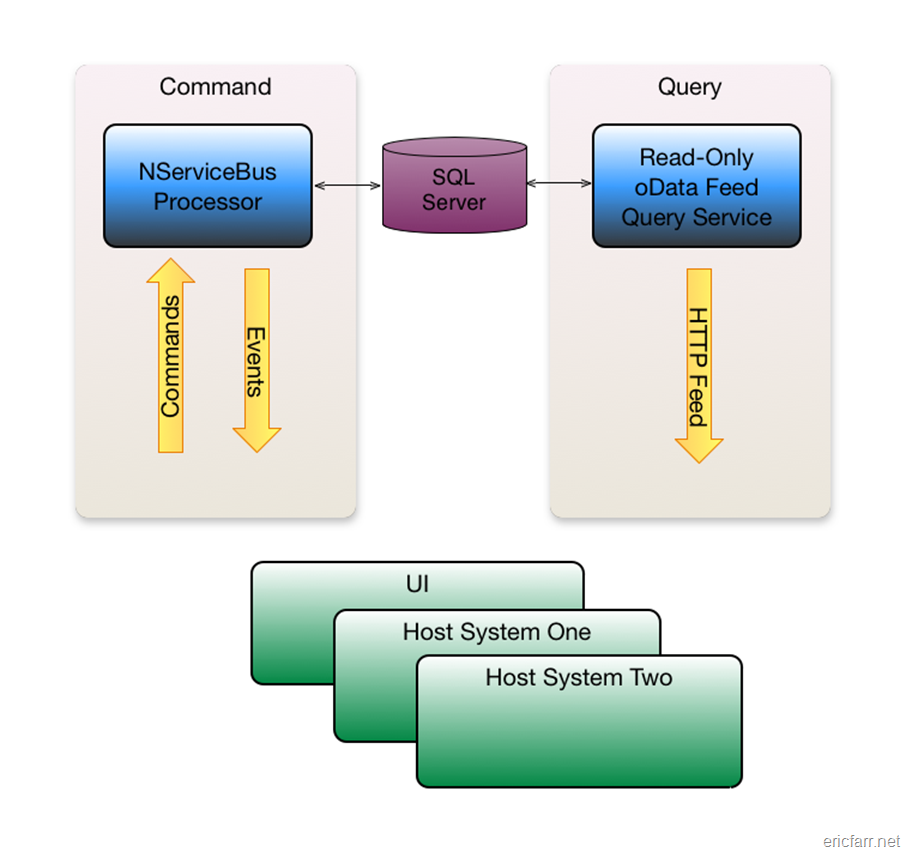

Fixing this problem meant an overhaul of the architecture, but the result was well worth the effort. In a nutshell, we redesigned the system to follow the Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) pattern.

Now all changes to the system are expressed as commands. Anytime the system changes, one or more events are published. Everything is commands in and events out. For reads, we added an Open Data Protocol feed that allows any application to query the data.

Figure 5: CQRS Design

Each of the applications and integration points is now sending commands to a central processing module (which may be dispatching to several machines). The commands express the precise intent of the sender of the command. So, UpdateWorkOrder becomes SetWorkOrderComment or SetWorkOrderDescription. Sending the command allows semantic meaning of the action to follow all the way through. We now log both the commands and the resulting events, creating a detailed audit trail of what happened within our system. This also allows us to better avoid merge conflicts because changes are more targeted with the specific commands.

Asynchronous Messaging versus Request-Response

Another huge win for this design improvement is in how it can scale. Building out the “write” side of the system with NServiceBus means that we can ditch all of the home-grown queuing, retry, and pub/sub logic between components. Now, all of our writes are async, forcing us to learn to deal without getting return codes or statuses from our calls. It took some getting used to, but is liberating in the end.

Our load testing shows that the system is now resilient to peak loads. The message queues swell temporarily, but everything continues to function.